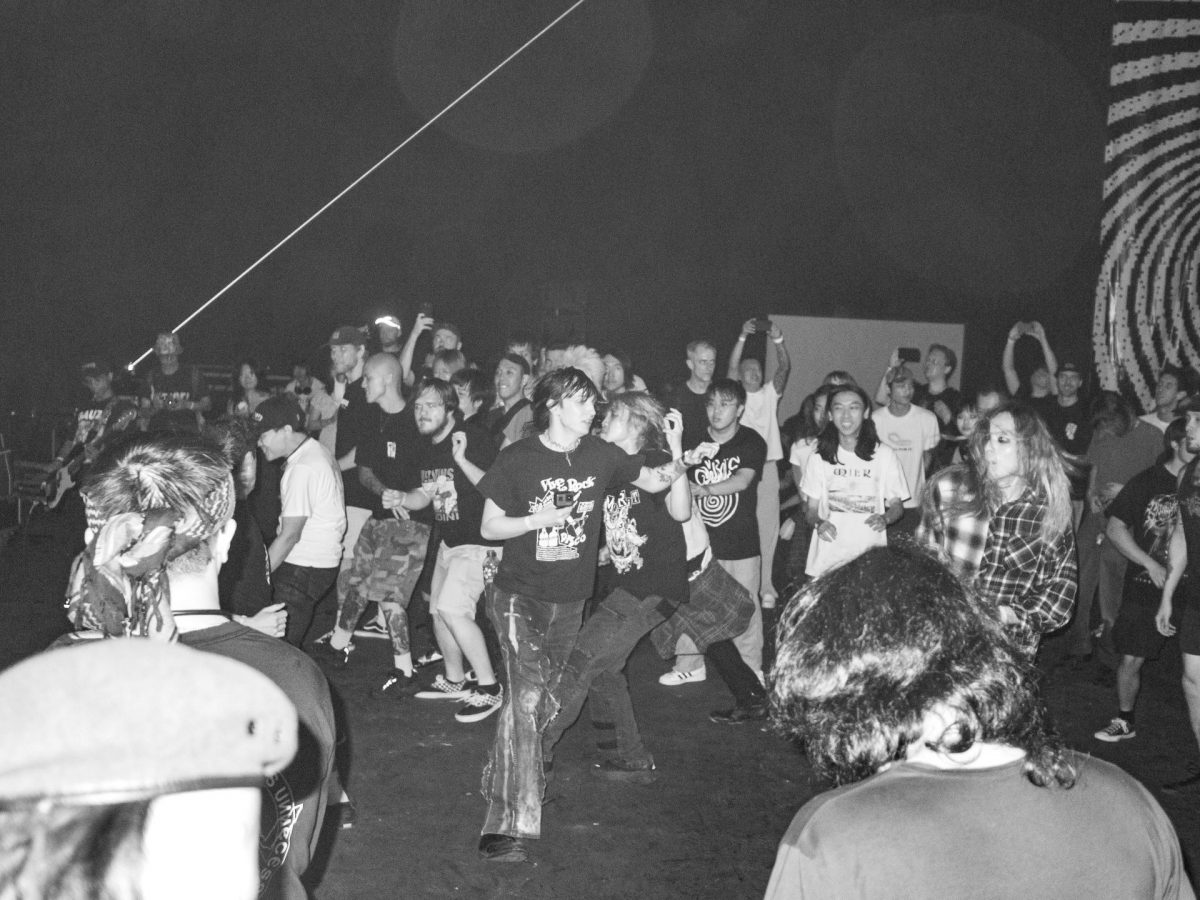

We visited the first edition of blankslate, an all-day DIY hardcore punk festival in Hong Kong.

Category: Editorial

MOST LISTENED SHOW 2024

MOST LISTENED SHOW 2024 (ACCORDING TO SOUNDCLOUD)

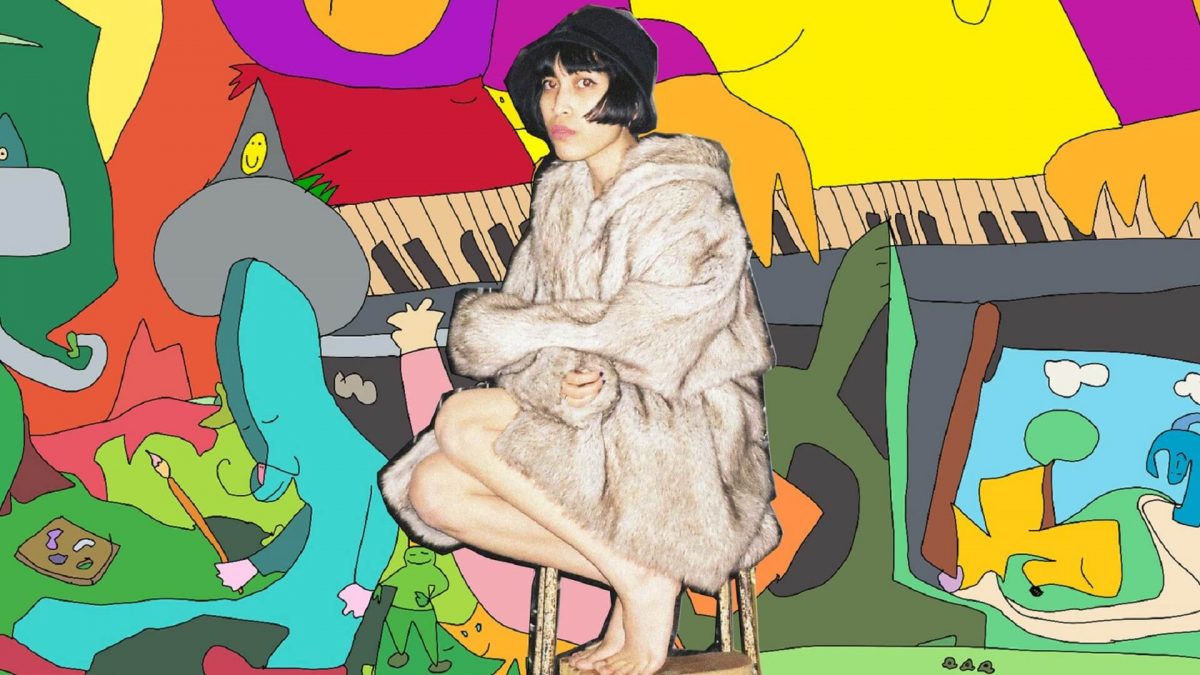

【檔案 PROFILE】Bungalovv

他的人生是以持續的創作去面對飄搖處境的故事。

【專訪 INTERVIEW】Yu Chao

人們實際上大多是暴力這個主題下的消費者,我們從新聞媒體或電影中,將某事物變得娛樂化、浪漫化,或著是把某個極惡放大到極致。

【專訪 INTERVIEW】Organ Tapes

Organ Tapes一直在唱,唱著那無人問津的歌謠。

【WHY RADIO?】— Anlin x Gribs

「我猜從某種程度上來說電臺更有人情味。不管是主播還是聽眾都可以從電臺收穫很多東西。」

【 WHY RADIO?】— Cheng Dao Yuan (TPE)

「對我來說,Mix就像是用「他人的情緒片段」建構成一段自己的訊息或是故事,以更加隱晦的方式去建立與他人的連結。」

【直播通知】HKCR PRES. Hounds of Pamir w/ Enclave (live)

12月11號晚上7點起於 HKCR.LIVE 直播 │ Stream live on HKCR.LIVE at 7P.M. HKT on 11th Dec

【專訪 INTERVIEW】Hiro Kone

「我感興趣的是詞句外的語言,是詞句間的空隙,是沉默,我對我們沒說出口和說出口的東西同樣感興趣,還有我們為何重複訴說某些東西。」

【WHY RADIO?】— RiceBaby

「我從不顧慮自己是否認同自己為一名藝術家或DJ ,我分享音樂的原因更多就是我覺得很好玩而且」